Underpass Art Installations

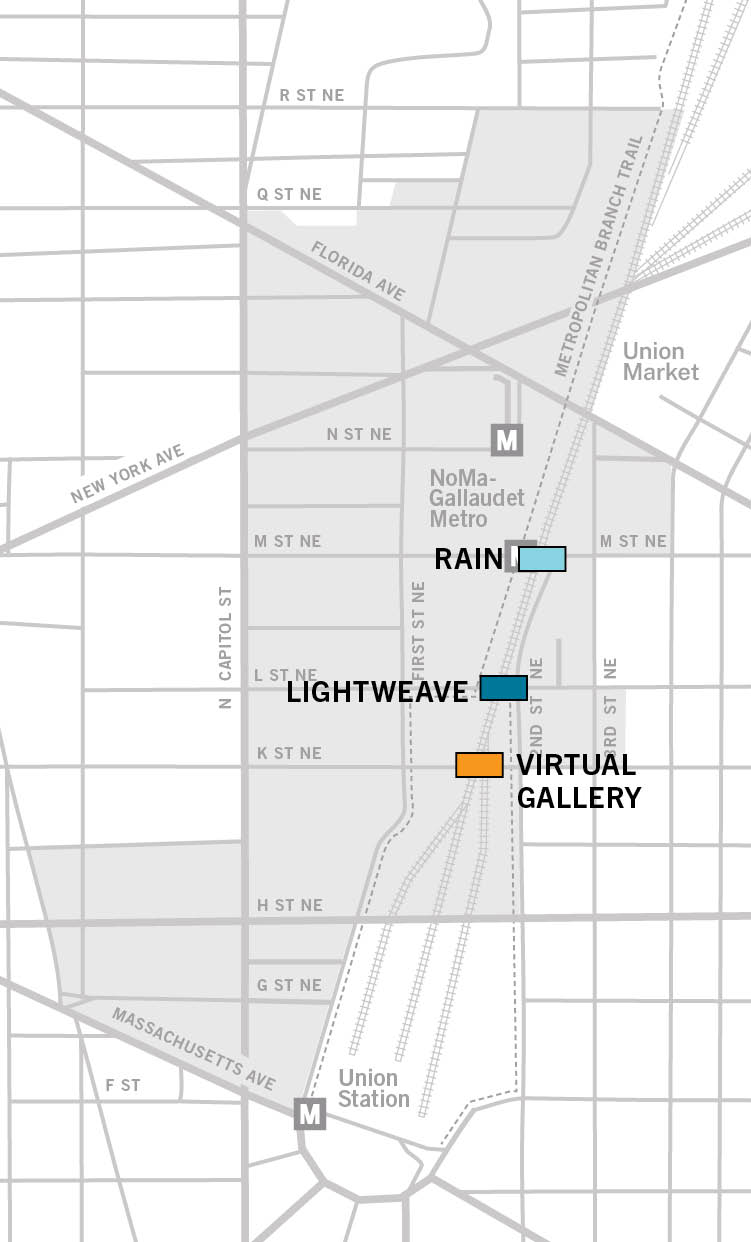

While the park projects reviewed above were the largest investments by the Foundation, its efforts were not limited to green spaces, as it was also able to improve the public realm more broadly, including three of the four connections between the east and west sides of NoMa beneath Union Station’s elevated railroad tracks:

- K Street between First and 2nd Streets NE

- L Street between First and 2nd Streets NE

- M Street between First and 2nd Streets NE

These spaces were identified in the 2012 NoMa Public Realm Design Plan as barriers or “disconnects” that needed to be addressed to promote neighborhood connectivity. Through the NoMa Parks Project, the Foundation strove to improve the condition of NoMa’s underpasses and enliven and beautify them using major art installations that would provide light, interest, and appeal.

These underpasses are critical connections between First Street NE — NoMa’s “Main Street” — and 2nd Street NE for the tens of thousands of residents and workers in and around NoMa. They provide access to area attractions including Gallaudet University, Union Market, the Swampoodles, REI, NPR, Wunder Garten, and the bustling H Street NE corridor, as well as new residential buildings and hotels on both sides of the tracks. In addition, they help connect the MBT to major bike lanes to the east.

The underpasses presented special challenges, given existing conditions and the variety of stakeholder interests. Significant underpass stakeholders include Amtrak, WMATA, DDOT and other city agencies, and NoMa community members. NPF worked closely with each of these stakeholders throughout the process to ensure that all of their engineering, mobility, access, and safety concerns were addressed.

The Foundation saw these spaces as opportunities to create “art parks” that would turn dank, dark, industrial underpasses into positive and safe experiences for all who pass through them: pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers. The commitment of NPF to include public art as a foundational element of its plan was deliberate. The vision supported the idea that public art not only enriches the experience of individuals, but that it is also a shared community experience.

Engaging artists to create installations required a great deal of effort to plan and implement. The unique conditions in each underpass first needed to be comprehensively documented to understand everything from size and layout to lighting levels, utilities, and vibration and water infiltration from the tracks above. In 2014, architecture firm RTKL completed a study documenting those conditions, paving the way for design proposals.

Through an international design competition, NPF sought to bring in the best ideas from around the globe. It launched the competition in April 2014, with 248 teams from 14 countries providing their qualifications to produce and implement underpass improvements. A NoMa Underpass jury reviewed submissions and determined the teams qualified to submit design concepts. The jury ultimately deemed 49 teams qualified to receive a Request for Proposals for specific design concepts; 10 finalists received honoraria, enabling them to further develop their design concepts for presentation to the community. This type of international design competition, one that also allowed for honoraria, might not have been possible in a standard public agency process.

On October 16, 2014, all final design concepts were presented to the community for input on aesthetics and functionality. Survey forms were available at the community meeting for the public to provide comments and ask questions about the submissions. Several of the finalists attended the meeting and responded to questions. Additionally, NPF used its community engagement website to present the final designs to the public and collect input on which design schemes were preferred. In all, more than 370 public responses were received and carefully considered.

The underpass transformation designs involved using light as art and art as light. Each is a complicated work of art and engineering, sometimes referred to as “infrastructural art,” that provide improved visibility within otherwise dark, unwelcoming spaces. One goal for this project, similar to the plan to improve safety by attracting more users and observers to the MBT, was making the underpasses interesting and attractive spaces which would also improve actual and perceived safety for pedestrians and bicyclists.

While the underpass makeovers once again exemplify how beautification can achieve functional as well as aesthetic goals, the underpass beautification journey that began with the NoMa Public Realm Design Plan was to prove far more challenging than expected. Beginning in the 2016–2017 timeframe, significant numbers of people experiencing homelessness found shelter from the elements in NoMa’s underpasses. By the time construction began on the second installation, Lightweave, in the L Street underpass, there were encampments in NoMa’s underpasses that complicated project construction and maintenance and undermined the goals of neighborhood connectivity and improved safety that these projects were intended to address. Then, in 2020, an explosion and fire destroyed nearly half of Lightweave.

During the pandemic, controversy, unsafe conditions, and the population of people living in NoMa’s underpasses grew. Providing services to people experiencing homelessness there became more difficult with the threat of infection, but the need to offer services to people living in the underpasses became ever more urgent. Several agencies and organizations, including the D.C. departments of Health and Human Services and Mental Health, the McKenna Center at St. Aloysius, So Others Might Eat, and the NoMa BID’s homeless outreach consultant, the h3 Project, bravely persevered through the height of the pandemic. They were responsible for caring for people’s physical needs, providing solace, and, without a question, saving lives during this period.

When Mayor Muriel Bowser, working through the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services, prioritized providing housing and services to all people encamped in NoMa’s underpasses, controversy swirled again regarding the best approach to balancing rights to use public space among neighbors. Beginning in 2022, with all people previously in NoMa’s underpasses now in safe housing, the NoMa BID and NPF undertook delayed maintenance and repairs, including to Lightweave. Ensuring that these important neighborhood connections can remain safe, appealing, shared public resources will continue to require thoughtful and constant attention.

FLORIDA AVENUE NE UNDERPASS

NPF continues to consider Florida Avenue underpass improvements to be important to enhancing connectivity within the neighborhood, especially pedestrian and bicyclist access to Union Market and beyond. However, given numerous calls for major changes to that underpass, and limited resource availability, NPF pursued other priorities.

NoMa Parks Foundation © 2024