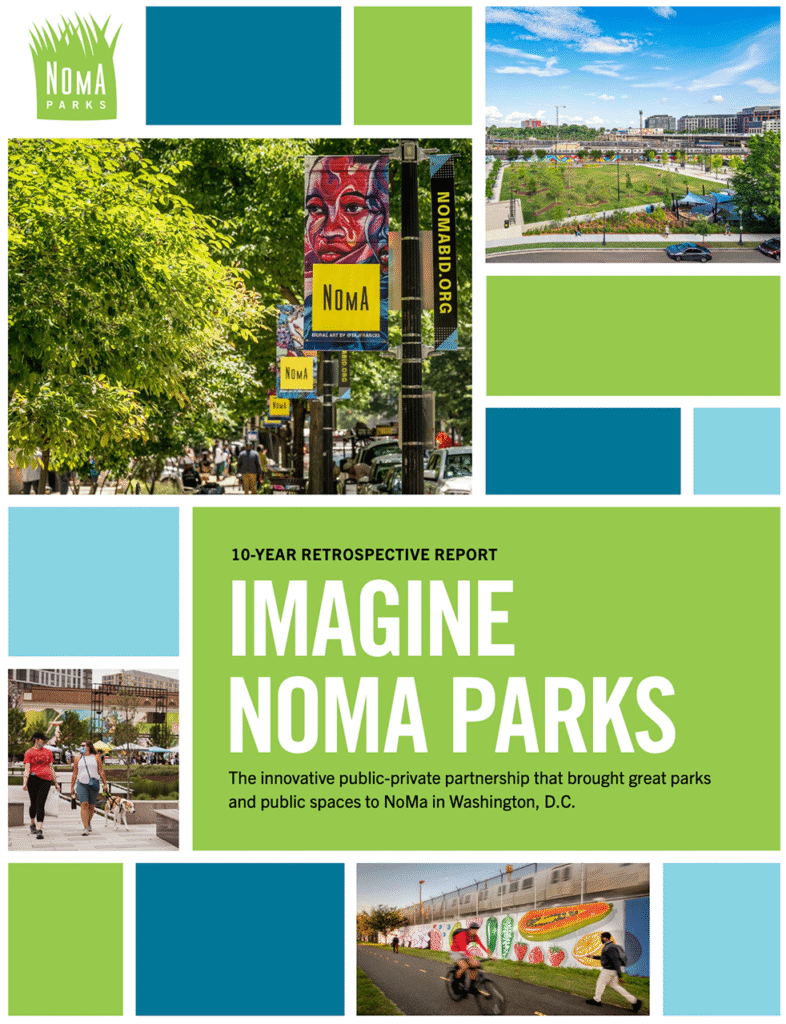

NoMa Parks Background

The NoMa Parks Foundation commissioned a report on the 10-year public-private partnership that brought great parks and public spaces to NoMa. Summaries of key findings from that Report are included here.

The beginning of NoMa as a mixed-use neighborhood can be traced back to the late 1990s, when the city was emerging from economic turmoil and a federally-imposed financial control board. You can learn more about the development of NoMa as one of DC’s great downtown neighborhoods in the Imagine NoMa Parks Report at pages 10-14 and by reading studies on the NoMa BID website.

NoMa BID Boundaries – These boundaries define a DC Council authorized taxing district where property owners have agreed to special assessment and do not define the limits of the NoMa neighborhood.

PUBLIC AND OPEN SPACES AS A CHALLENGE TO SUCCESS

When the Metro station opened in 2004 and the BID was created in 2007, NoMa had no accessible public parks. Parks and public open space is not merely an amenity — they are critical to physical and mental well-being

NoMa’s lack of public and open spaces became evident in the mid-2000s. Several studies and reports made the case that a truly vibrant and healthy neighborhood needs to provide workers, visitors, and, especially, residents of NoMa with places for relaxation and recreation. For more information see the discussion at pages 11-12 of the Imagine NoMa Parks report.

NoMa’s development shifted from office to residential in the early 2010s, and its population grew rapidly. Stakeholders and District leaders realized the urgent need to create parks and open spaces in the neighborhood. But nearly all the land in NoMa was privately owned, values were escalating, and developers large and small were buying properties in the neighborhood.

But time was of the essence, because nearly all the land in NoMa was privately owned, values were escalating, and developers large and small were seeking to secure properties in the neighborhood.

TACTICAL URBANISM AS A SHORT-TERM SOLUTION

While the work to plan, fund, acquire, and build parks took many years —the NoMa BID recognized the opportunity to use temporary, “tactical urbanism” efforts to activate vacant sites public spaces. The BID’s efforts began early on through the creation of a series of temporary sites for NoMa Summer Screen, now called CiNoMatic, Wunder Garten, and the Lunch Box pop-up.

Words Beats & Life – 15,000 square foot ground mural at NoMa Summer Screen temporary site – now NoMa CNTR.

The Imagine NoMa Parks report highlights the NoMa BID’s effective use of tactical urbanism to meet the needs of the growing NoMa neighborhood:

“One criticism of tactical urbanism is that it is temporary and can often leave communities and neighborhoods unchanged after the project is over. Yet the NoMa experience shows that when it is done thoughtfully and with a longer-term view, tactical urbanism can help bridge community needs while more permanent solutions are pursued. And, as will be shown, these events helped initiate community engagement and guide long-term approaches to parks and public spaces. In NoMa, what started as short-term activations became longer-term successes — witness the Wunder Garten beer garden, which is still in operation seven years later in 2022, in a much larger space at the corner of L and First Streets NE.”

Learn more at page 13 of Imagine NoMa Parks.

© Sam Kittner/Kittner.com Wunder Garten’s first popup in NoMa at Constitution Square.

NoMa Parks Foundation © 2026